Another Twenty-Six Gas Stations

2014

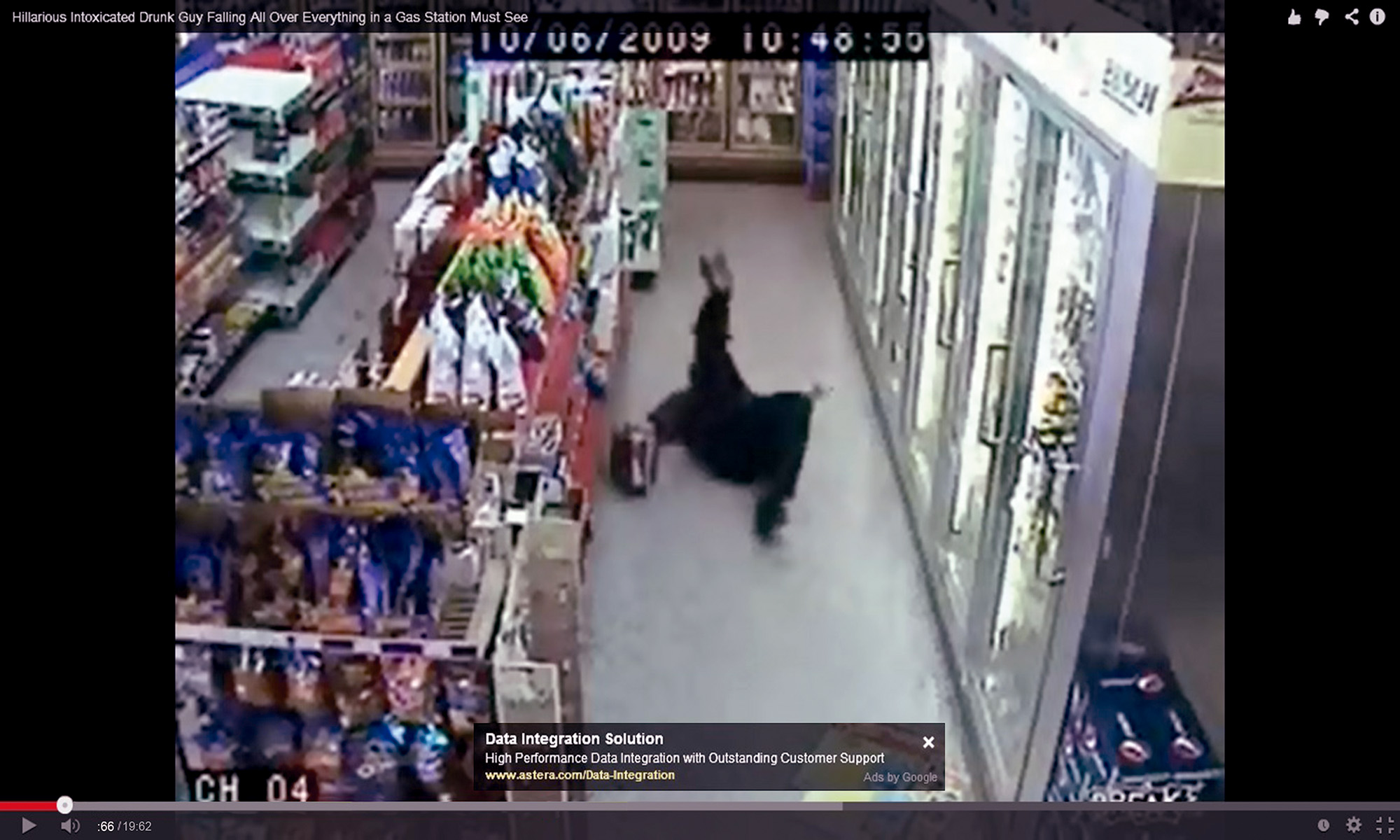

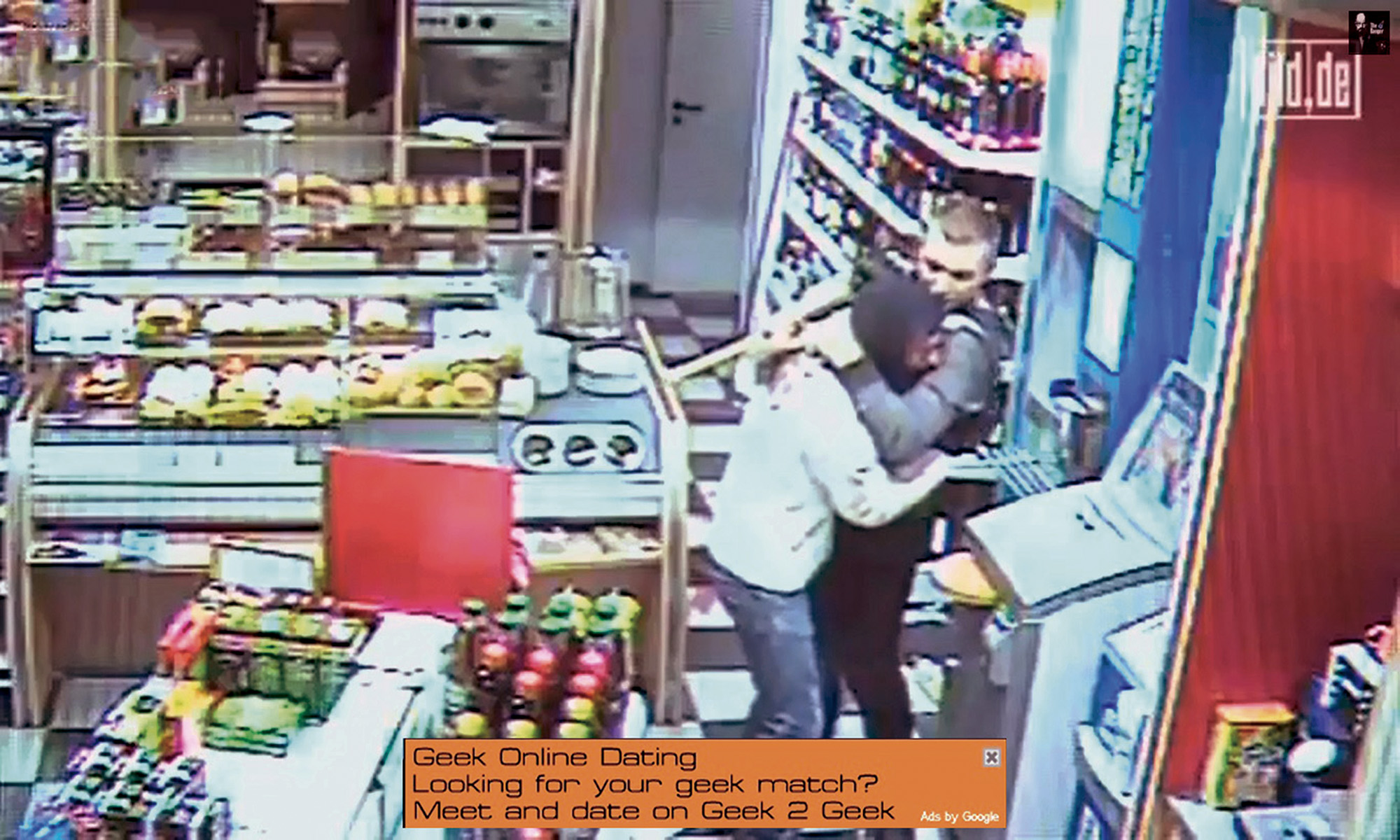

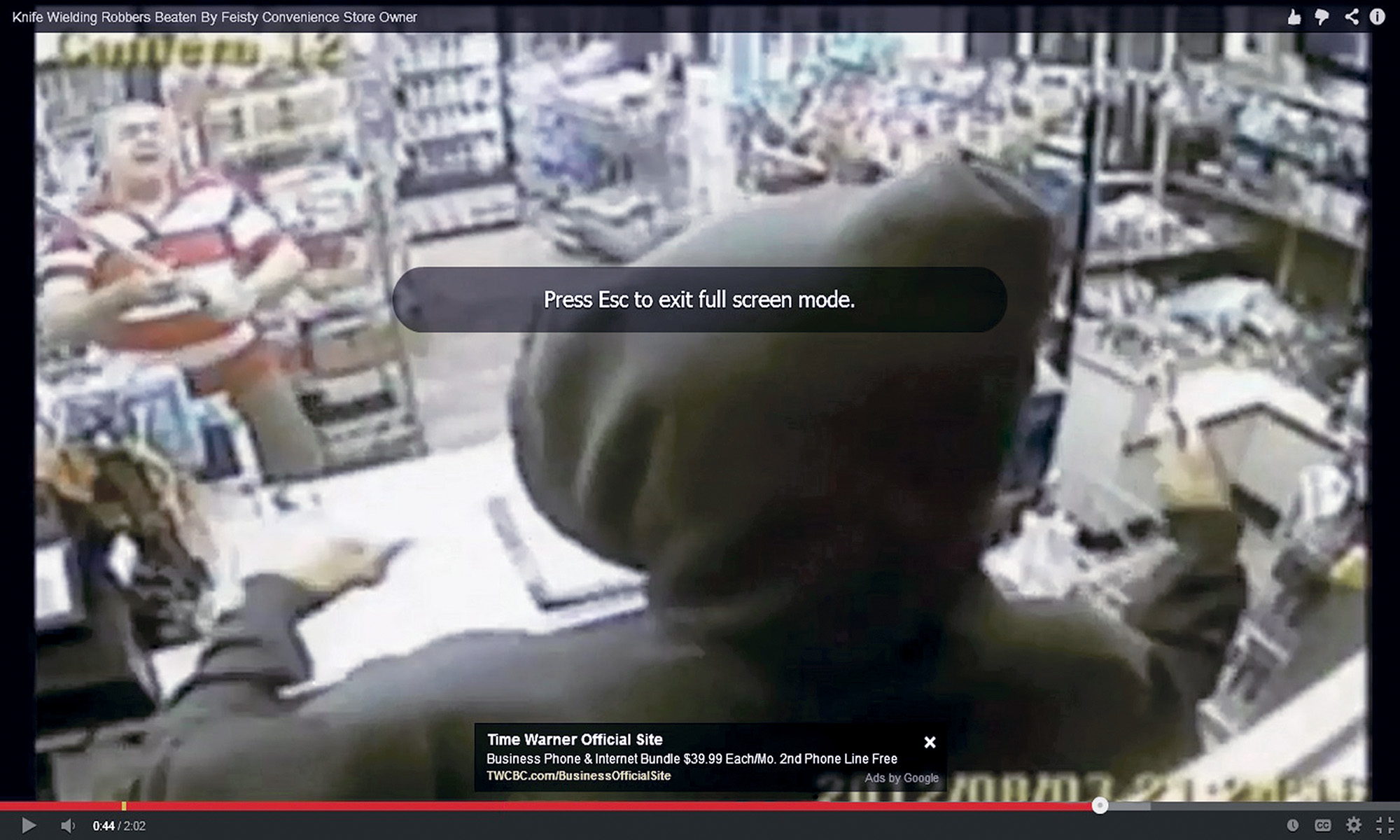

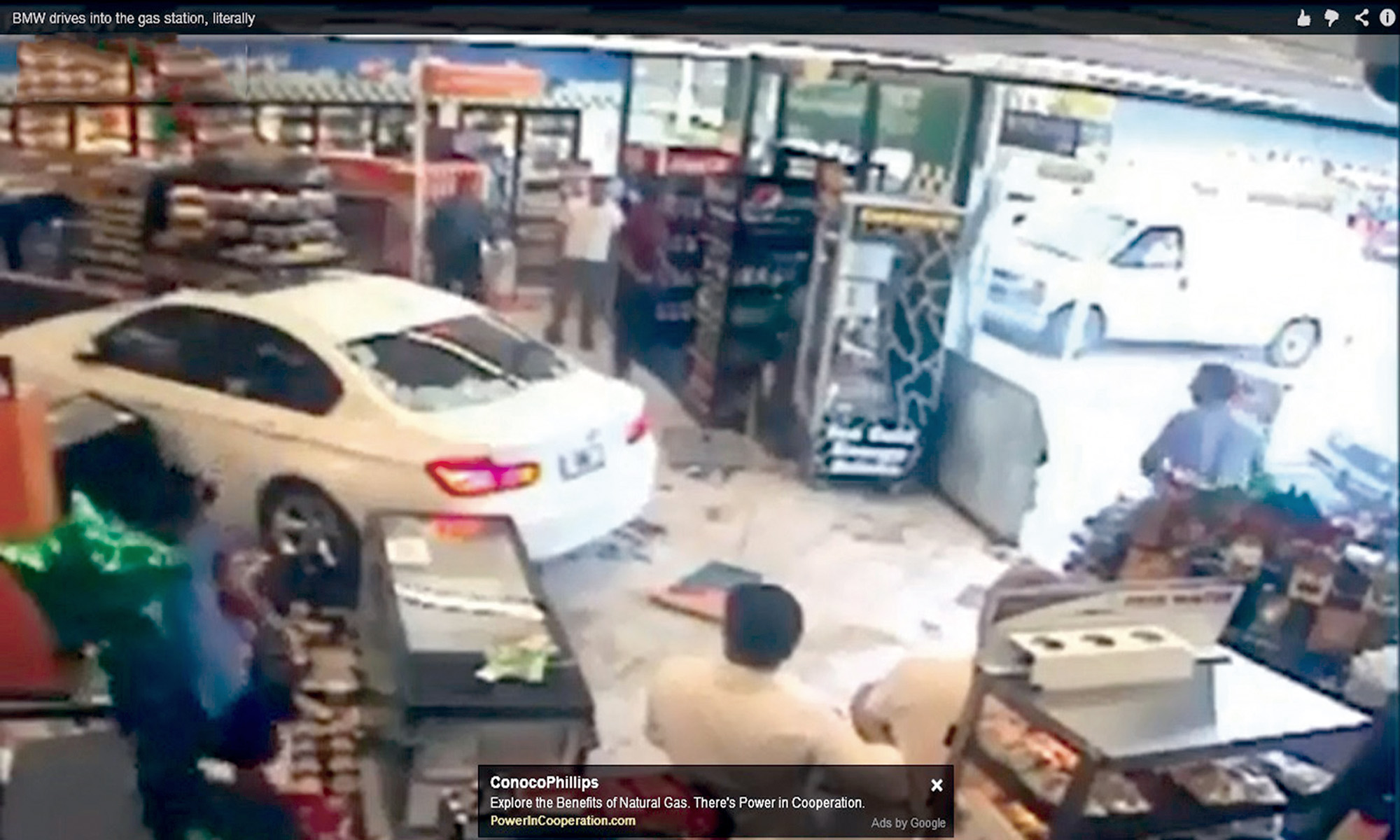

Another Twenty-Six Gas Stations is a new media artist book comprised of twenty-six screen captures culled from gas station surveillance videos found on YouTube. The book blends notions of surveillance, crime photography, advertising, and found text; which together form an incisive dark-humor commentary on advertising and violence within the framework of online consumption.

Fifty-one years after the publication of Ed Ruscha’s seminal book work, Twentysix Gasoline Stations, Another 26 examines how the American identity has shifted from the idyllic media messages and car culture of the 1950s and 60s, to the coarse post-9/11 age we occupy today.

Within the book, the image-text relationships work to form interweaving layers of meaning and interpretation. The sequence ties together formal properties, textual interplay, narrative sequences, as well as several discrete visual puns and references to Ed Ruscha. The book’s elements create a meditation in morality and mortality, which challenges the viewer to either succumb to her own fascination with the violence depicted, or to look beyond the surface to discover the critique embedded within.

Reviews

Musee Magazine - Review by Kate Marin

Who Needs Another Photo Blog - Review by Christer Ek

ActuPhoto - Review by Estelle Magnin

Exhibitions

Schaulust - Photoforum Pasquart, Biel Switzerland. Curated by Danee Panchaud.

Ed Ruscha Books & Co. - Gagosian Gallery, Beverly Hills, CA.

Afterword by Lance Speer

Ed Ruscha and Gregory Eddi Jones

Gregory Eddi Jones’ Another Twenty-Six Gas Stations has as its direct antecedent and inspiration a book entitled Twentysix Gasoline Stations (National Excelsior Press, 1963) by renowned photographer and painter Ed Ruscha. While produced over half a century ago, a brief consideration of Ruscha’s work in the context of its era remains quite relevant to the interpretation of Jones’ work presented here.

When Ruscha was photographing his twenty-six gasoline stations he was doing so in the “present tense” of the early 1960s. This period in American culture has been characterized as a “quieter, simpler time” (the Cold War possibly going nuclear notwithstanding), as it predated the coarsening of the culture we have come to know today. The Kennedy brothers had yet to be killed, and soon-to-be-assassinated Martin Luther King and Malcolm X had yet to bring the struggle for racial equality to the forefront of American culture. Massive U.S. troop escalations in Vietnam had not yet materialized, and college campuses were still years away from becoming cauldrons of counter-culture protest and havens for sex, drugs and rock & roll. In looking at Ruscha’s Twentysix Gasoline Stations today there are certain art historical, anthropological, and even nostalgic aspects to his work. Yet rather than relics of some bygone era, Ruscha’s edifices were active, living elements of the culture of the time. They were important way stations, albeit in the middle of nowhere, along the storied Route 66, a venue made internationally famous through its then-prevalent role in defining American “car culture.”

What made Ruscha’s work gain importance during the 1960s and the years since was its position within the continuum of Conceptual Art and Pop Art, two movements that have remained influential up through our current Internet Age. When seen through these prisms, Ruscha’s commonplace gasoline stations transcended the notion of merely representing aspects of car culture and its role in forming the American Identity of the 1960s. They became much larger signifiers - banal icons of America culture in general. Many of the same conceptual / iconic phenomena pervade Jones’ images of that bastard offspring of the 1960s gas station – the convenience store. Yet in Jones’ work the new American Identity is characterized not by quaint ideas regarding American car culture but by the mayhem and anarchy of the more malevolent culture of the new millennium. The quietude of Rusha’s conceptual inventory of mundane black & white gas stations from the 1960s is replaced in Jones’ work by a full-on assault of color, violence, spectacle, and commercialism - all documented by the ever-present surveillance camera.

In Jones’ book we are confronted, via YouTube video screen captures, with the here-and-now of the omnipresent convenience store, a locus within the culture with which we all can identify. In these appropriated images, shelves are packed with the colorful detritus of the everyday – chips, soda, Snickers bars, breath mints, beer, cigarettes, beef jerky, cheap sunglasses, as well as the perennial Slurpees, scandal-mongering tabloids, shitty stale pizza slices and 3-day old hotdogs. We are all familiar with this place, this Kwikie Mart cornucopia of plenty, this icon of American junk culture, and that’s the point. Extending this line of thought, the ubiquity of the convenience store echoes the omnipresence of the YouTube video, the medium with which the assorted and sundry attacks and vandalism in such establishments is transmitted to the world and, by extension, into Jones’ work. It has been said that during the era of the 1960s Americans were “addicted” to their cars. In our era it is an absolute truth that Americans are now addicted to junk food - available all day / every day at your local convenience store – and perhaps even more addicted to online media.

When considered in this light, the “old banality” of Ruscha’s gas stations gives way to the “new banality” of the convenience store, its colorful junk food, the increasingly common crimes committed within, and the 24/7 accessibility of such crimes through YouTube, the latter rapidly becoming a most potent contemporary opiate of the masses.

Weegee, The Andy Griffith Show, and Law and Order

Throughout the 1930s and 1940s Weegee (Arthur Fellig) worked as what we now call a photojournalist, specializing in crime scenes, murders, suicides, fires, and all manners of chaos, death and destruction. His prowess with the arts and alchemy of photography allowed him to capture much more than the physical delineations of a crime scene. With a rather clear-eyed documentary style that bordered on fine art, if not crossing over completely, Weegee’s images often maintained an uncannily humanistic element. The emotion of a scene, often seen in the survivors, the onlookers, sometimes even the otherwise inanimate victim, all resonate with profound empathy.

In Jones’ YouTube screen grabs of active crime scenes there seem to be no bullet-riddled bodies lying on the pavement, no pools or smears of blood, no crying survivors, all of which often characterized Weegee’s photographs. There is also none of the empathy found in Weegee’s best work. Rather than documenting the aftermath of hooliganism and criminality, Jones’ has selected images that allow us to witness the act itself at its precise documentary (and evidential) moment in then-real time. We remain safely removed from the malevolent forces that occupy the familiar stage before us, yet we’re present none-the-less. Here the warm, inviting, vibrant colors of the convenience store betray their environment, as the coldness of violent crime permeates scenes made even starker by the grainy and choppy nature of the dispassionate surveillance camera footage grabbed to create these images.

While Weegee’s signature photographs of crime scenes and deaths from the 1930s and 1940s were in many senses quite disturbing, it must also be remembered that this was an era often characterized by the nature of its “law abiding citizenry.” The subsequent decades saw a continuation of relatively good-natured homespun mores, of Ozzie and Harriet in the 1950s and of Leave It to Beaver in the 1960s. During the same early 1960s of Ed Ruscha’s gasoline stations most people’s exposure to crime had come from sanitized episodes of Dragnet in the 1950s, and from watching simpleton crooks in Mayberry get their comeuppance from bumbling Deputy Barney Fife or good ol’ soft-spoken Sheriff Andy Taylor on The Andy Griffith Show in the 1960s. In today’s moment, instead of watching warm and fuzzy crime and punishment in 1960s black & white, many contemporary television programs reflect the Law and Order franchise paradigm by showing mangled bodies, severed limbs, disfigured faces and a host of other blood-soaked crime-induced traumas, all to the point where this sort of violence and spectacle has become the norm. Yet the difference between the scripted violence and props department body parts of fictional TV and what currently resides on the Internet involves, of course, reality. Through such channels as YouTube, Jones’ media of choice, we can watch true-to-life people being continuously held-up, assaulted, shot at and otherwise terrorized at the local convenience store, all to the point of ubiquity - if not banality.

What Jones offers us, then, is a “just around the corner” experience, one made possible by the all-seeing, all-knowing surveillance camera.

Surveillance Culture and Crime Porn

Chances are that on any given day, including the day you acquired or downloaded this book, you were surveilled many times. Surveillance cameras are everywhere - used in retail “loss prevention” roles, for traffic monitoring, in home security systems, even as “nanny cams.” Yes, it has come to that. It’s often said, including within in this short essay, that we live in the Internet Age. This is of course true, and there are both benign and certainly benevolent aspects to the concept of the Internet Age with its instant access to information, news, sports, weather, shopping. The Surveillance Age, though, is perhaps an equally pertinent and descriptive nomenclature for our post-9/11 times, even if it seems so much more ominous as it harkens back to the predictions of Big Brother from Orwell’s 1984. Surveillance Age currently encompasses everything from the present situation in the North Korean police state, the National Security Administration abuses perpetrated by the American government, traffic intersection monitoring in cities, all the way down to the checkout at Starbucks and everyone’s every movement inside and outside of convenience stores.

Isolated instances of surveillance footage, captured through a usually passive, unmanned, and banal system of image making, often become culturally important when something actually happens. While not a direct product of surveillance culture, the iconic Falling Man image, a still photograph by Richard Drew of a victim (identified as possibly being Jonathan Briley) of the 9/11 terrorist attacks against the World Trade Center, still points to the importance of news cameras and instantly transmittable images in terms of both image production and image consumption in our digital age. Similarly, the Boston Marathon bombers were identified within days of their anonymous 2013 attack via the internet broadcast of surveillance video. While filmed for completely different reasons in a different era, had JFK not been assassinated its more than likely that Abraham Zapruder’s 8mm color film from that sunny November day in Dallas in 1963 would have remained an anonymous home movie rather than perhaps the most famous and studied piece of camera imagery ever created. As with all of this imagery - Weegee’s photographs, a 9/11 death plunge, the Zapruder film, and Jones’ appropriated hold-ups - we can’t look away. It is, after all, Crime Porn.

In Crime Porn we’re all insatiable voyeurs, and in the case of Another Twenty-Six Gas Stations, Jones is our benevolent pimp. He has scanned YouTube and found these moments of mayhem, violence and anti-social behavior and brought them to us neatly packaged and wrapped in the niceties of his diminutive book. Using the raw material he finds on the web he creates his own narrative through image selection, editing, and sequencing. No longer are we looking at the placid silvery documents of Ruscha’s commonplace gasoline stations. Instead we are witness to the rough grainy color feed of surveillance cameras as they capture the worst of human nature, raising a host of dynamic questions: Who got shot, either by a perp, a clerk, or by the responding cops? Who died? Who was traumatized? How? What were the underlying motives behind such acts/attacks? And, perhaps most importantly, who is the audience for these YouTube moments? To answer these questions we must return to that oft-repeated refrain by Walt Kelly of Pogo comic fame: “We have met the enemy and he is us.” By isolating moments of mano-a-mano violence, Jones takes otherwise neutral, documentary moments and calls us out for the animals we are, and this mirror is not our friend.

This Unadulterated Violence is Brought to You by Brand X

Jones has stated that he sees the “deadpan vernacular” of Ruscha’s photographs as a point of departure – an opportunity to update / restate / make new certain ideas and visual strategies that Ruscha could not have even dreamed of in 1963. This position, however, prompts a significant question: Where does Jones’ creative and aesthetic vision reside? These days almost everyone has or has access to a computer and/or a smartphone and/or a tablet. Anyone could go online and find similar images. So just what defines Jones’ position as artist in Another Twenty-Six Gas Stations? Ruscha took his “real camera” out into the “real world” and made photographs of “real things.” Yet rather than going out and shooting actual locations and events as was done by Ruscha, Jones sits in front of his computer and lets the world come to him. What we are experiencing, then, is perhaps the ultimate expression of the “decisive moment” being completely trumped by the “decisive edit,” as Jones appropriates existing imagery from his computer and brings his subject imagery into his - and our - living room. As with the silent social commentary of Lee Friedlander, Gary Winogrand and Diane Arbus, Jones’ collected imagery brings us face to face with who we are, and it is precisely the banality and the ubiquity of his imagery that gives it its power. Jones’ “art,” then, is in seeing the aesthetic potential in all of this – his collecting, arranging and presenting “automatically recorded imagery” for us to contemplate, to laugh at (yes, some images are actually pretty funny), to agonize over, and to question ourselves.

While privy to the action in each image via their inclusion in Jones’ book, we as audience are as yet removed from it by a number of orders of magnitude. First, the surveillance cameras take Jones’ place as photographer and, by extrapolation, our place as direct witnesses. Secondly, the individual who edited the original footage exercises an editorial authority by selecting what imagery will be uploaded to his YouTube account, his blog, his website. Then Jones exercises his own edit of these images to determine which frame grabs he is initially interested in, and finally through his direct mediation comes the finished edit and the attendant sequencing that appears in this book. Yet in spite of all these degrees of separation we are drawn into the immediacy of the individual images and the narrative as a whole to the point where we can feel a true first-person identification, and much of this has to do with both the all-too-familiar gas station / convenience store as setting, and YouTube broadcast as delivery mechanism.

Another quite significant element of Jones’ images is the appearance of advertisements in a number of his screen grabs. As a perfect example of the ridiculous banality of contemporary culture, small banner ads promoting “Geek Online Dating” services, stain remover, and sports team paraphernalia - amongst other things - resonate with undeniable absurdity when seen in the context of these anti-social images. These embedded artifacts seem rather random, but just how did such mundane banners get placed on these images of extreme violence and mayhem? In point of fact, “Company X” (insert advertised company name here) did not have a representative authorize the use of a business name or ad copy as a banner on any given image. Instead, online advertisements such as these were placed according to algorithms based on keywords and demographic information provided by websites that track one’s browsing history.

These ads, then, are themselves borne of our Surveillance Culture. As products of the online realm - virtual billboards on the digital highway that recall the physical billboards of Route 66 in Ruscha’s Twentysix Gasoline Stations – the importance of these ads in Jones’ screen grabs resides not only in the absurdity of their inclusion, but in the implied multiplier effect of surveillance itself. Here the online viewer of these images of surveillance is him/herself surveilled. Taken to the next degree, if one purchases either an eBook or hard copy of Jones’ Another Twenty-Six Gas Stations through PayPal - the transactional hub of Jones’ sales - or through sites such as Amazon.com, that transaction is itself surveilled via algorithms that track such activity. The ultimate experience, then, is an infinite Möbius strip of surveillance culture. In regard to all these myriad levels of surveillance, and in the parlance of scholarly art historical research and the rhetoric of cultural anthropology, one can only think, “What the fuck?!”

All in all, what is happening in this work is indeed loaded with meaning, insight, and opportunities for interpretation. Appropriating Ed Ruscha’s classic trope in terms of general subject matter (twenty-six gasoline stations), the vernacular of his delivery system (the artist book), and a cold and impartial style (of both Ruscha’s vision and that of the unmanned surveillance camera), Jones has sought to capture a similar “snapshot” of contemporary culture and place it front and center for us to consider. As mentioned, the ubiquity and banality of Ruscha’s work defines a particular point in the development and expression of Conceptual and Pop Art, and in many ways Jones’ work fulfills his own stated interest in “continuing the dialog by building upon the conversation started by Ruscha” by hitting the refresh button, as it were, on his original idea. In the end this work serves as incisive color commentary on our digitally mediated and constantly surveilled culture, and God help us all.